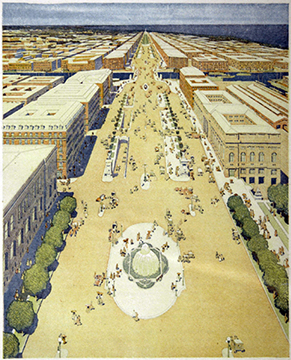

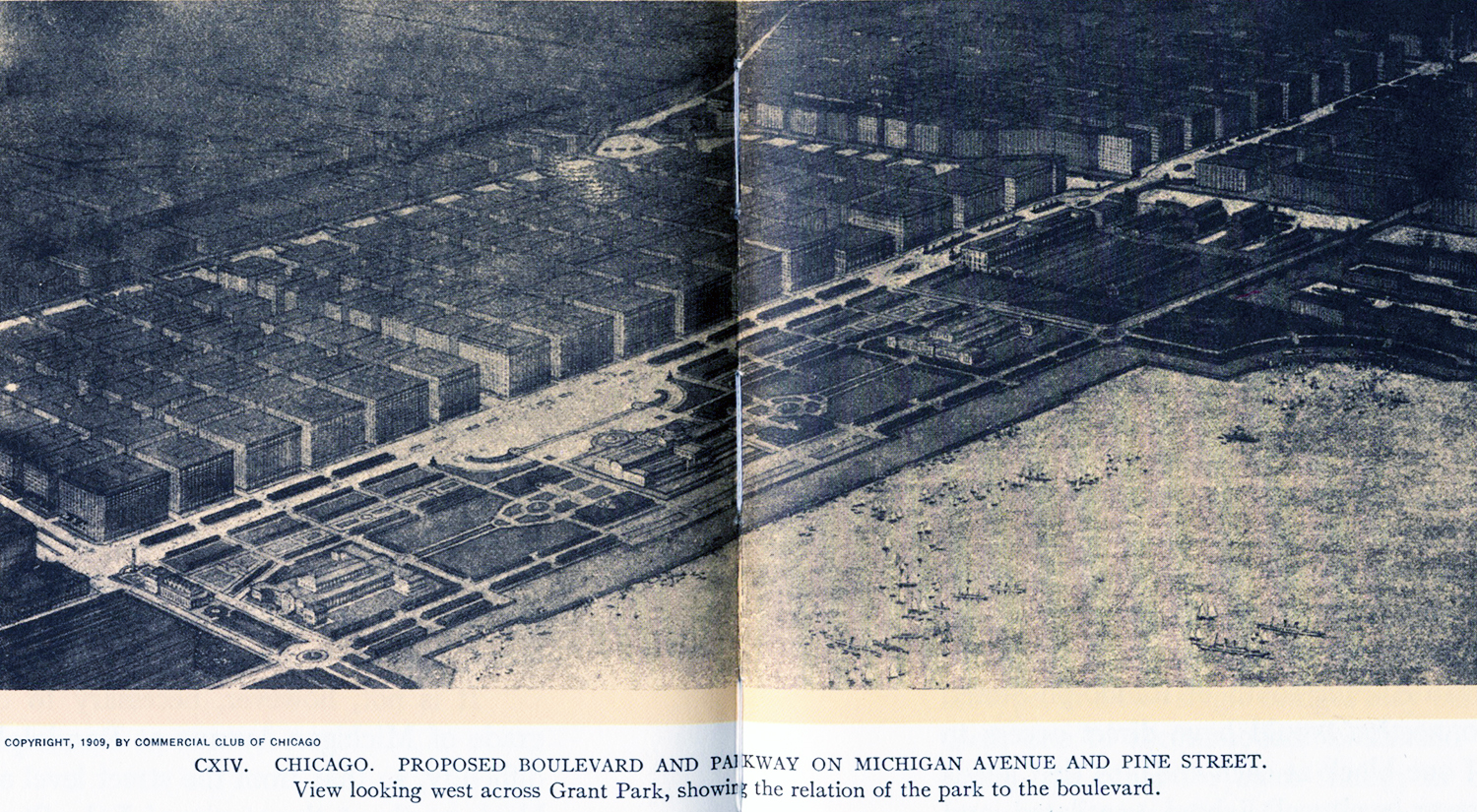

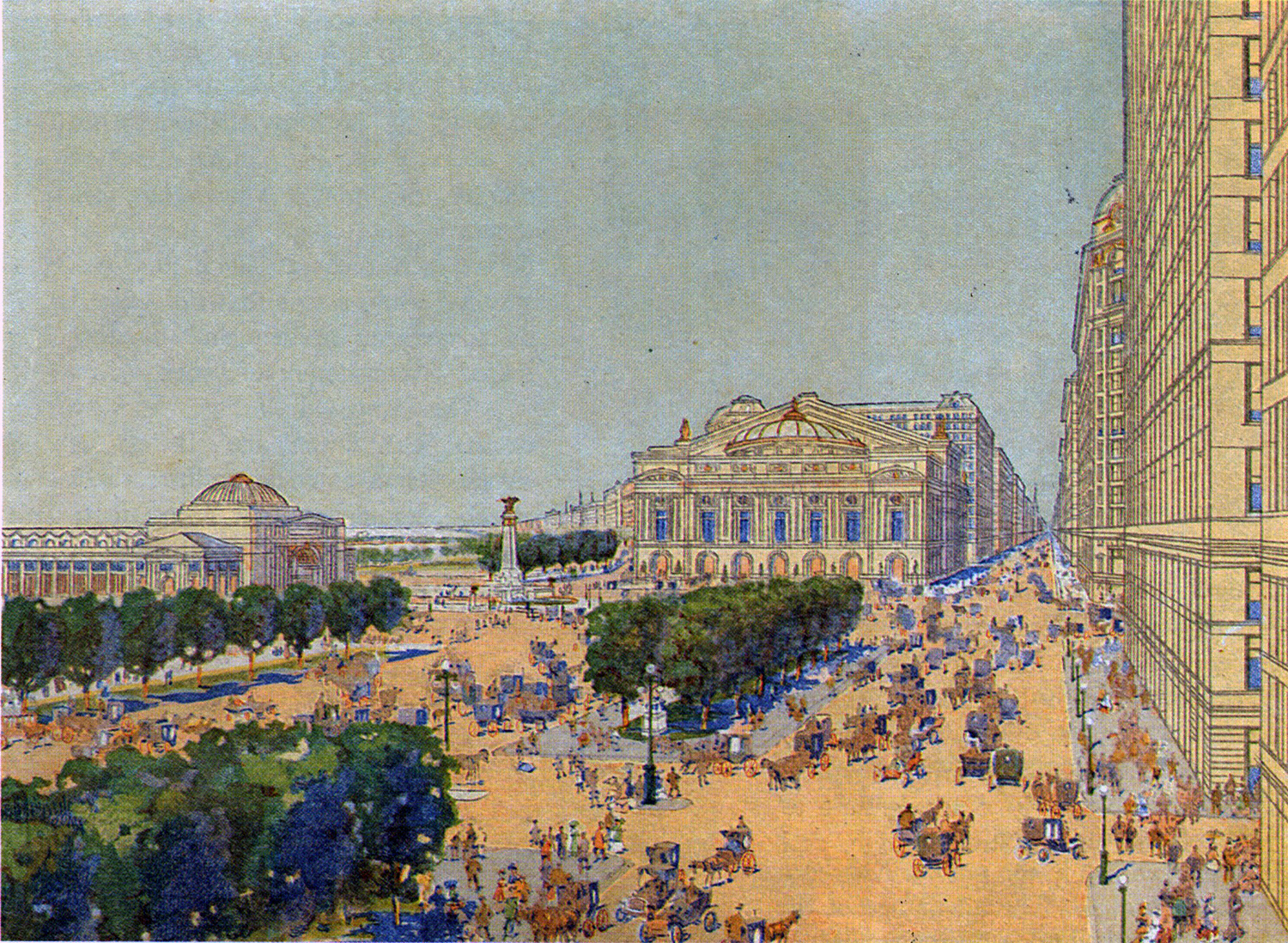

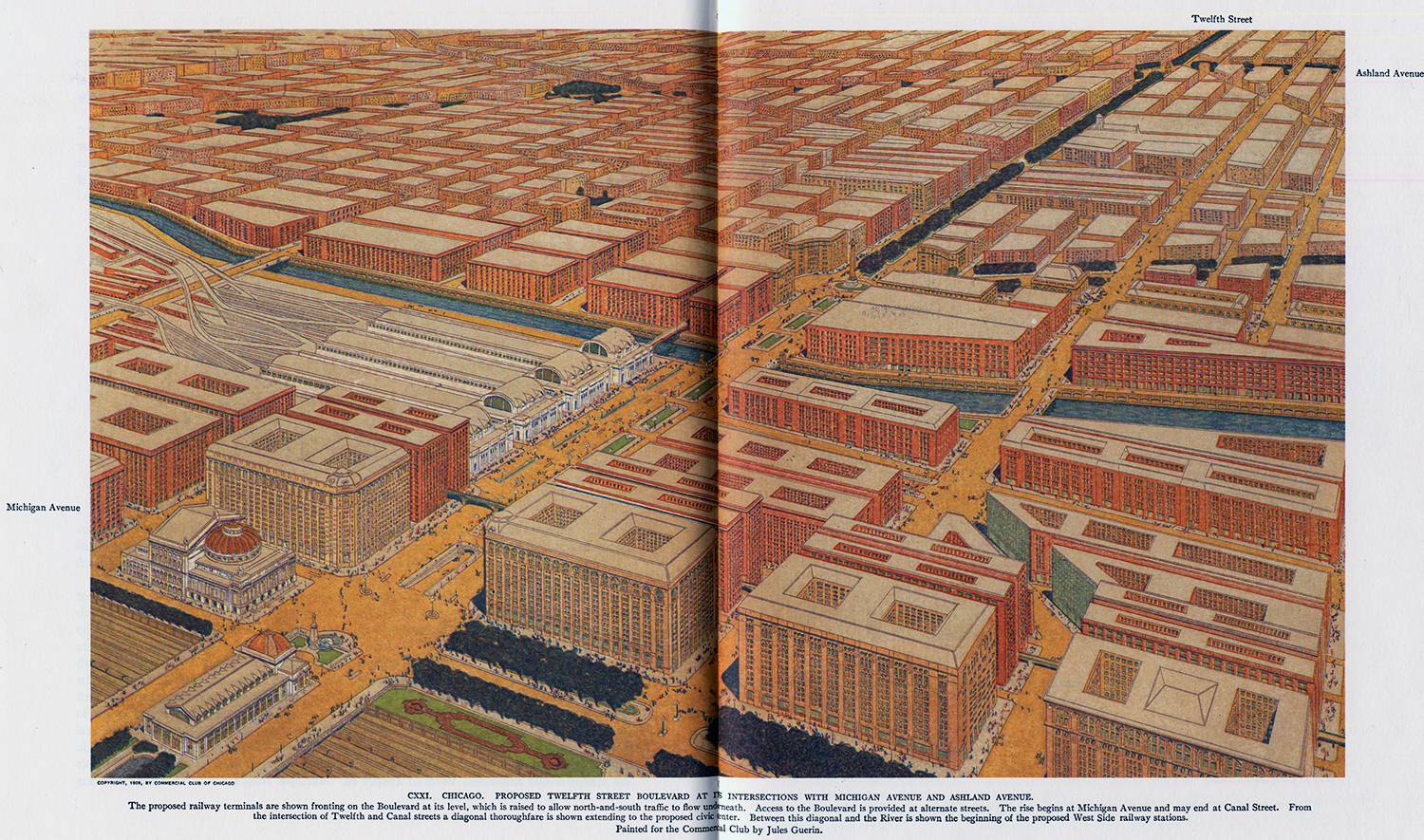

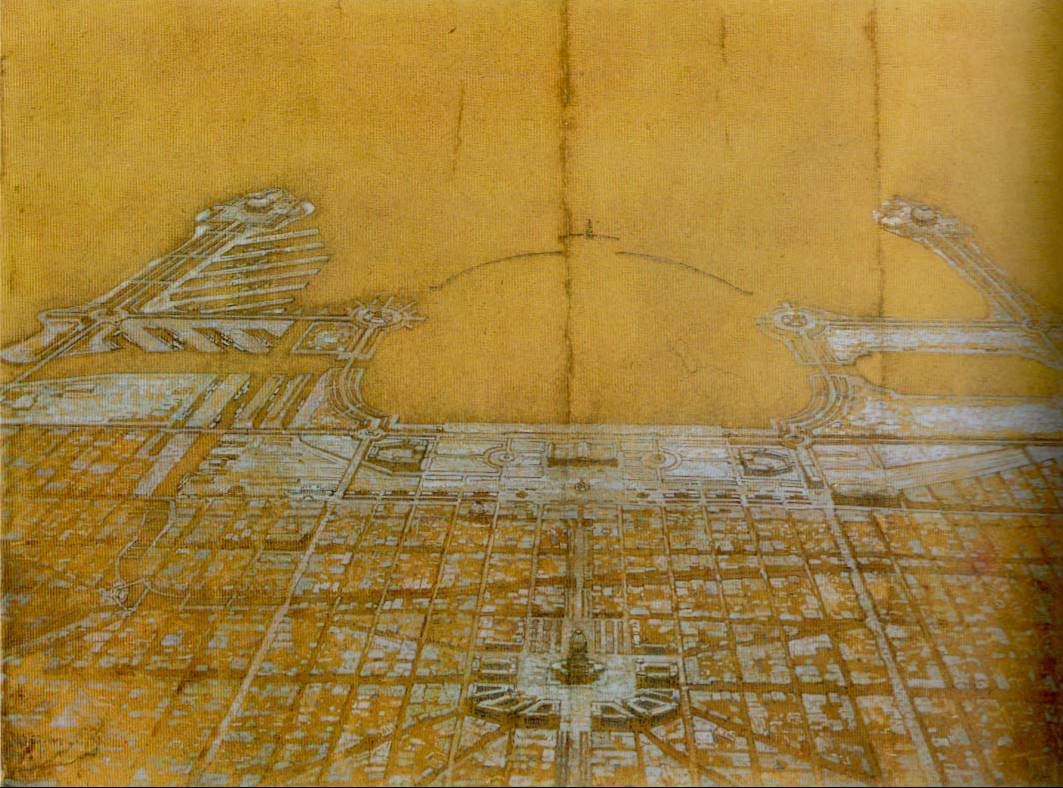

Left: Selected Plates with summary captions, from Daniel Burnham’s and Edward Bennett’s 1909 Plan of Chicago:

— Daniel Burnham, Plan of Chicago, 1909

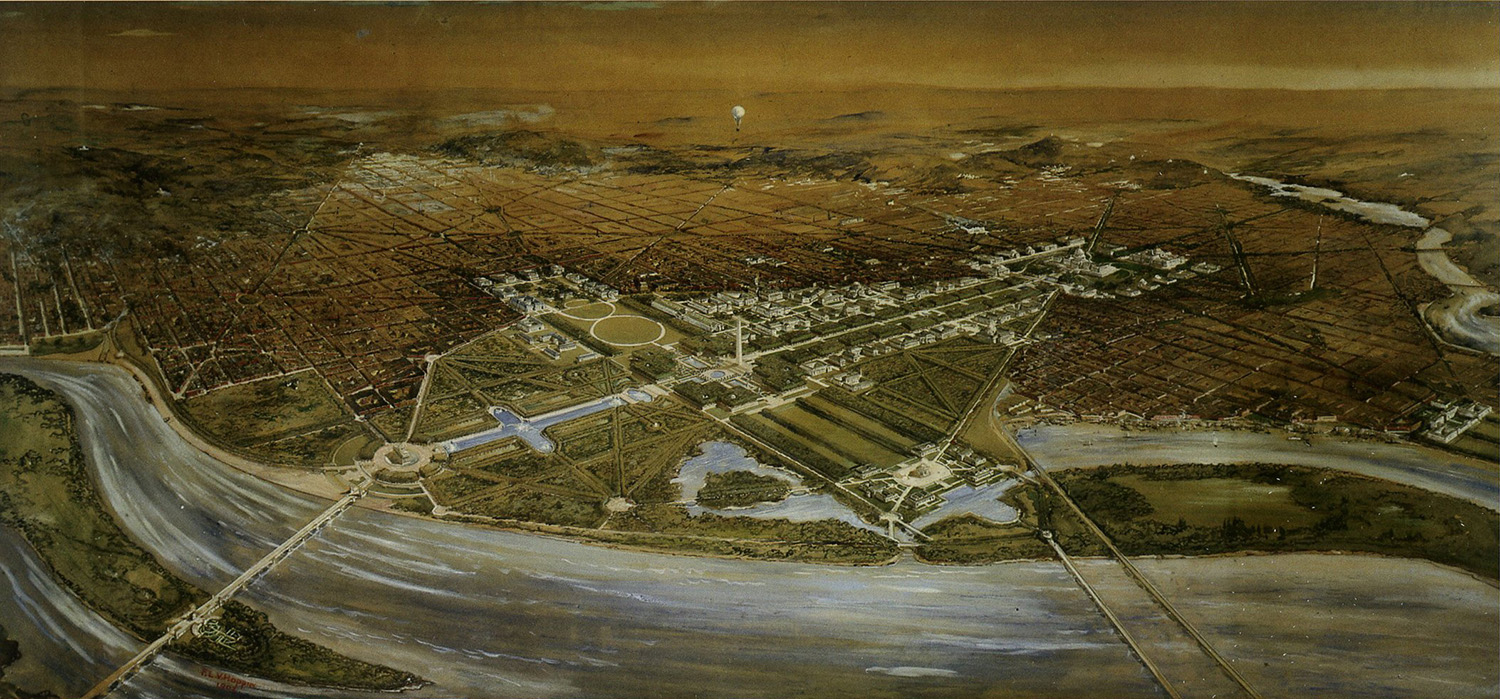

Already a successful architect in partnership with John Wellborn Root, Daniel Burnham’s career as a city planner took off following his success as Director of Works for The Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and his 1901 work for the Senate Park (aka McMillan) Commission in Washington, DC. Burnham’s Plan of Chicago (with Edward Bennett) followed his smaller scaled (but still large) urban design proposals for Cleveland, San Francisco, and Manila and Baguio in The Philippines, which together represented and helped establish the American City Beautiful Movement and its classical humanist urbanism as the leading school of city planning through The Great Depression and up to World War II.

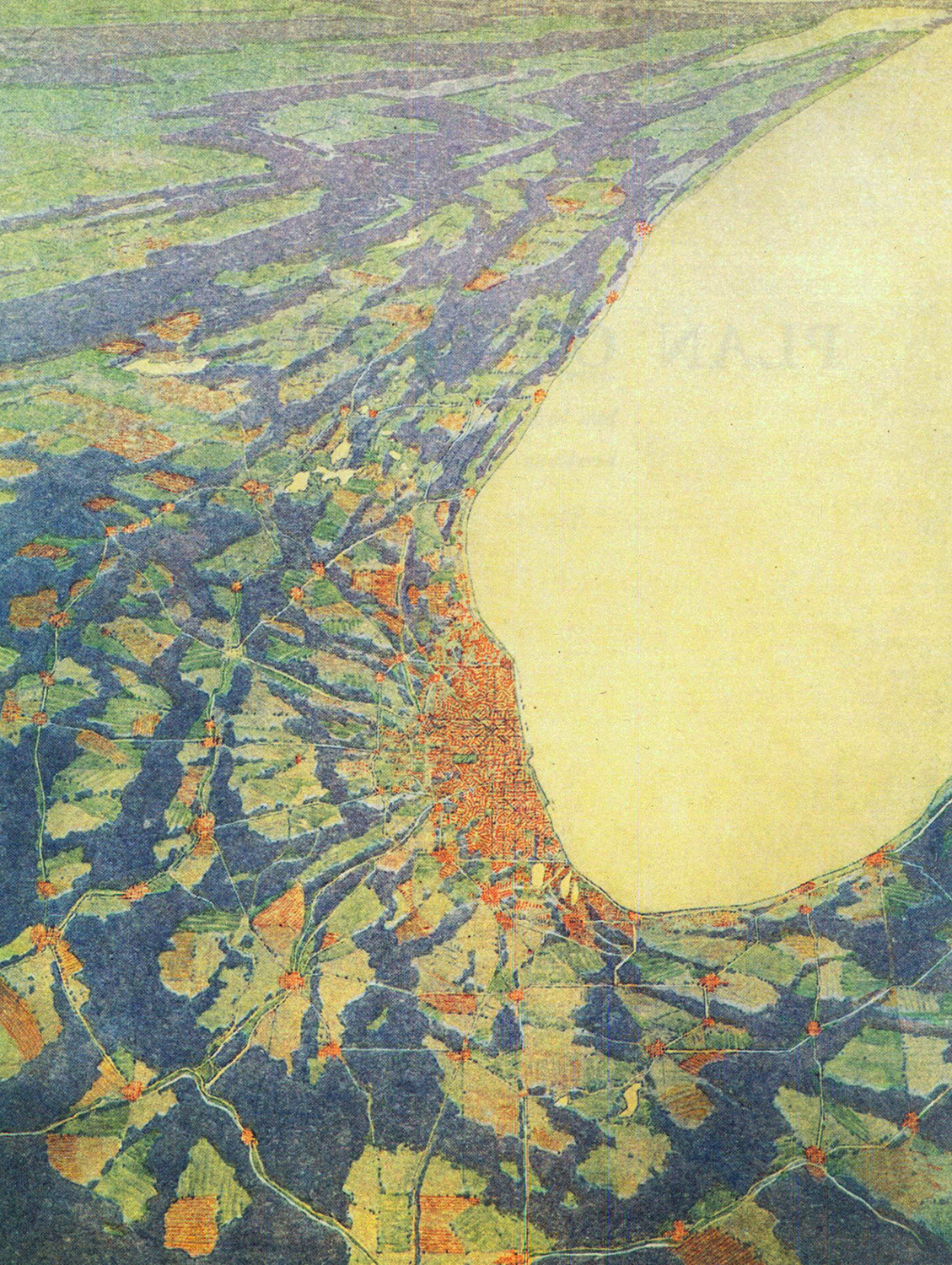

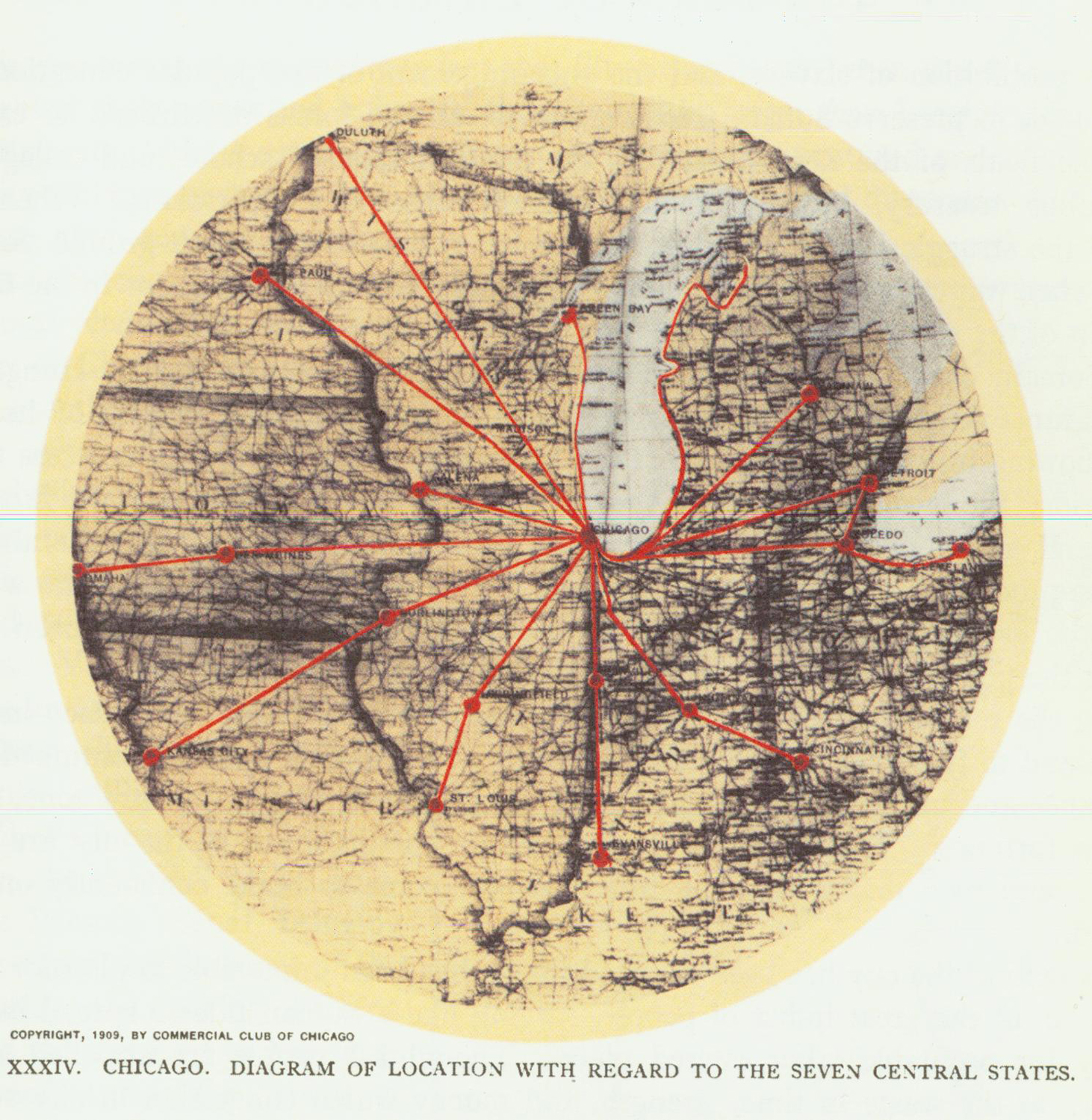

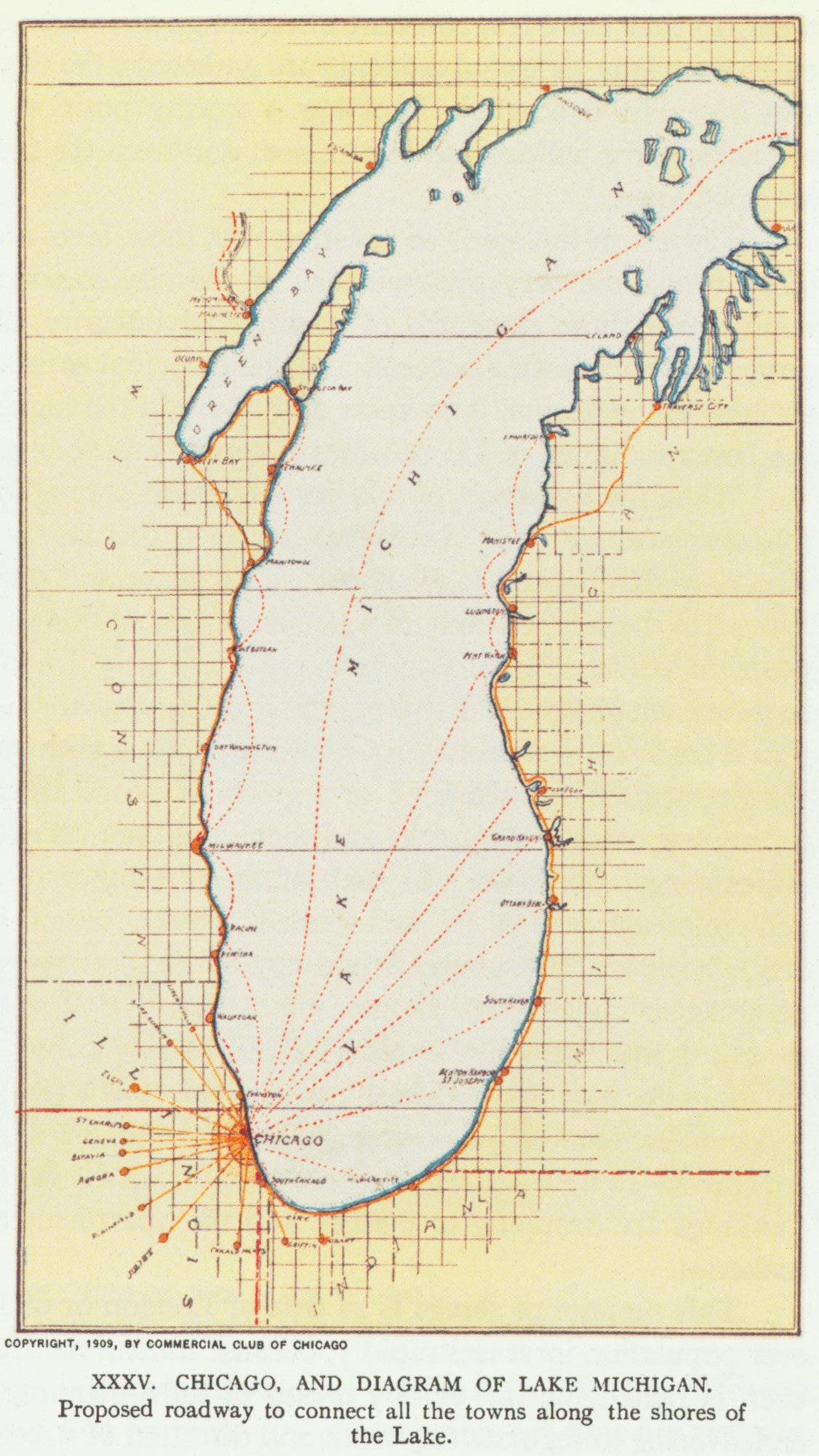

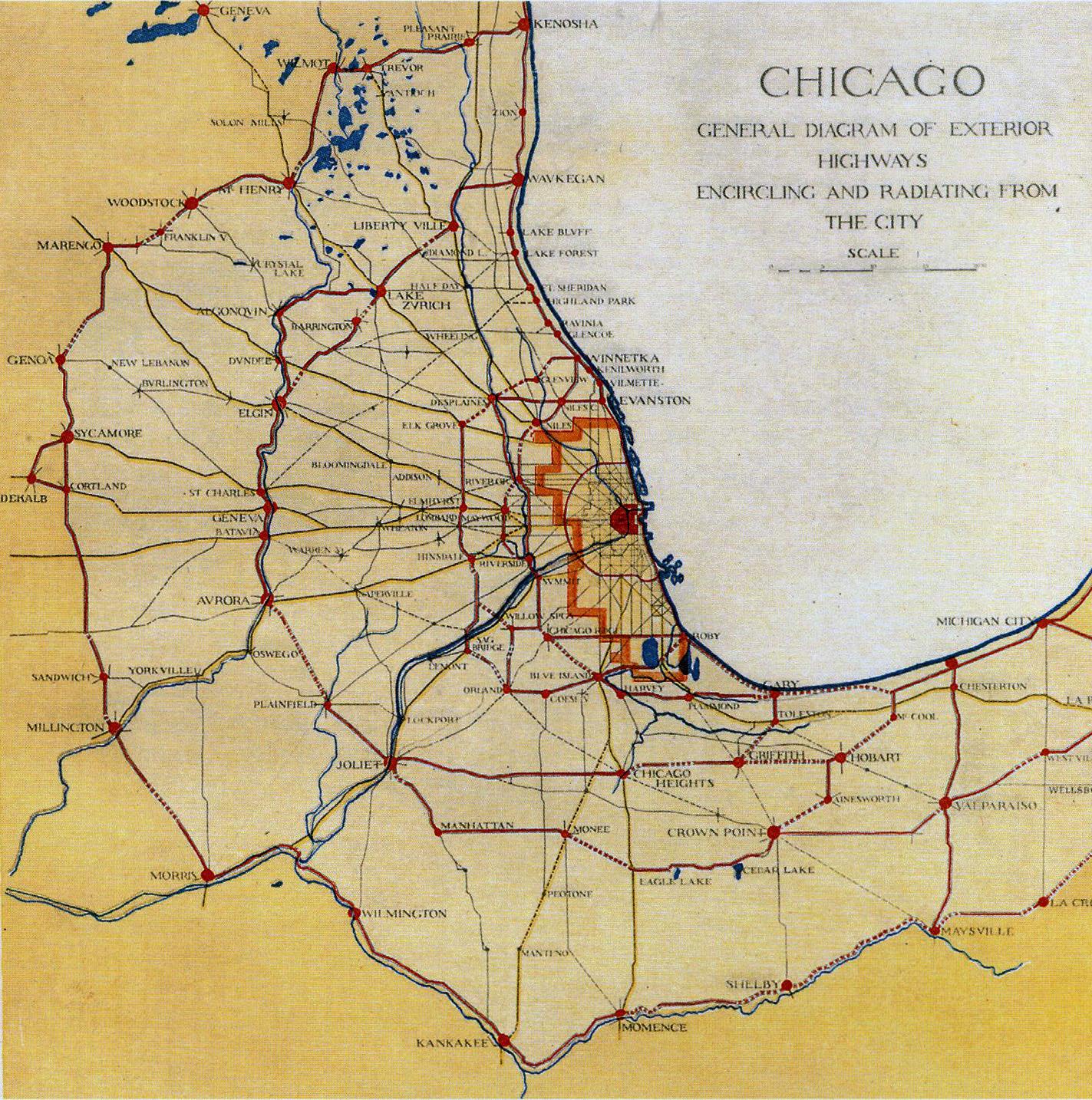

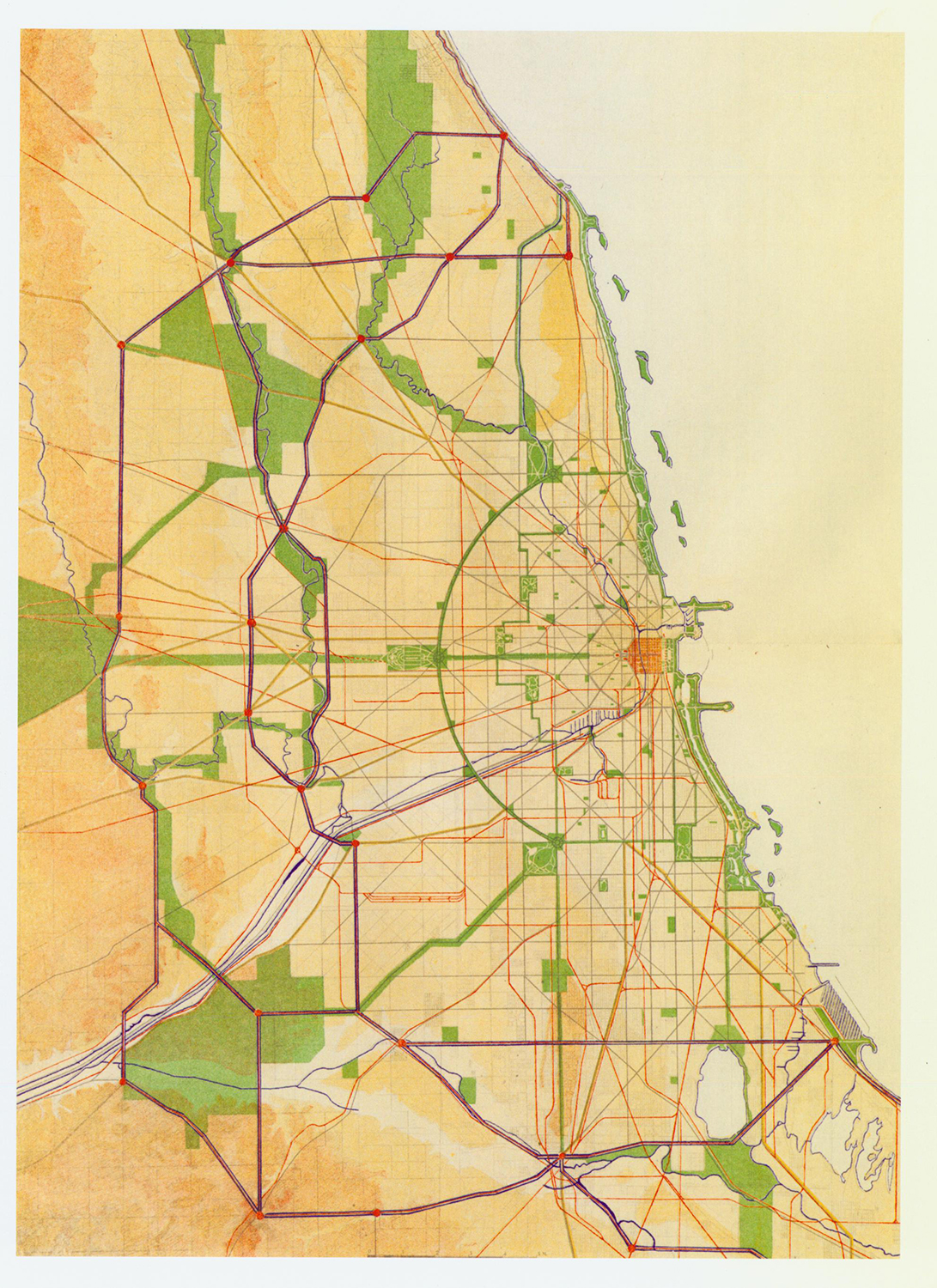

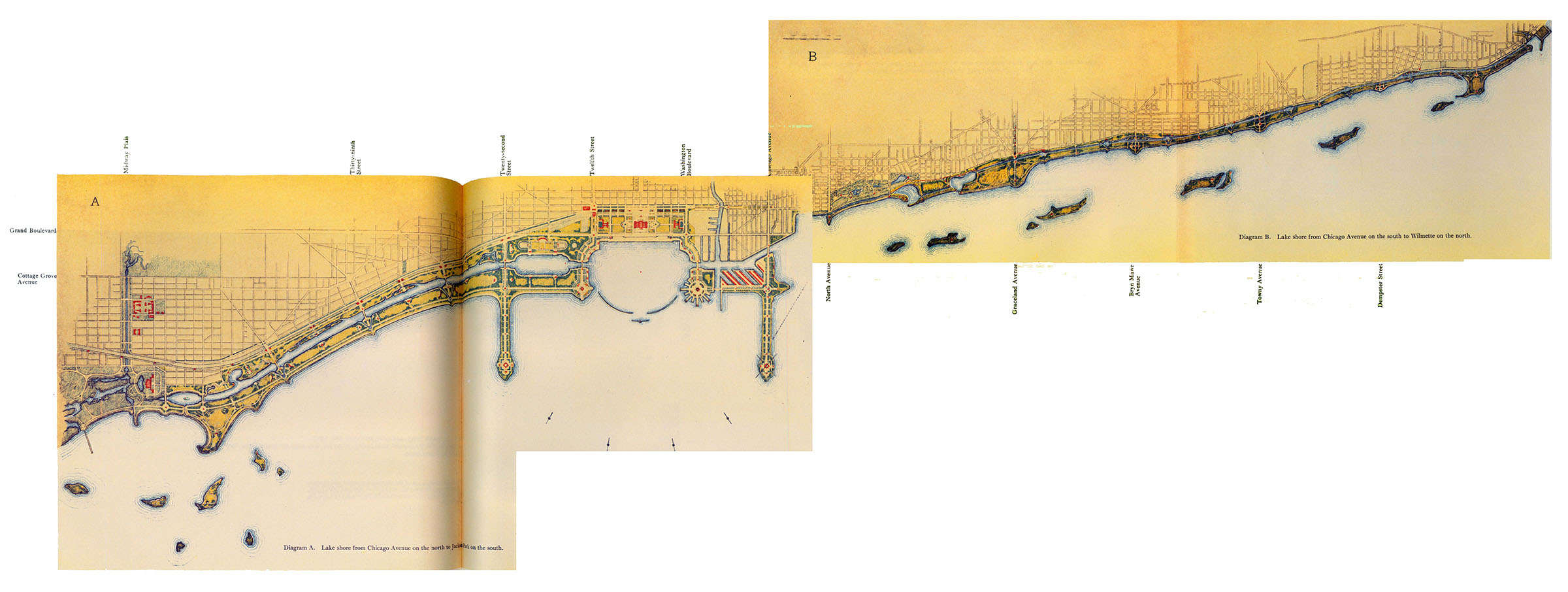

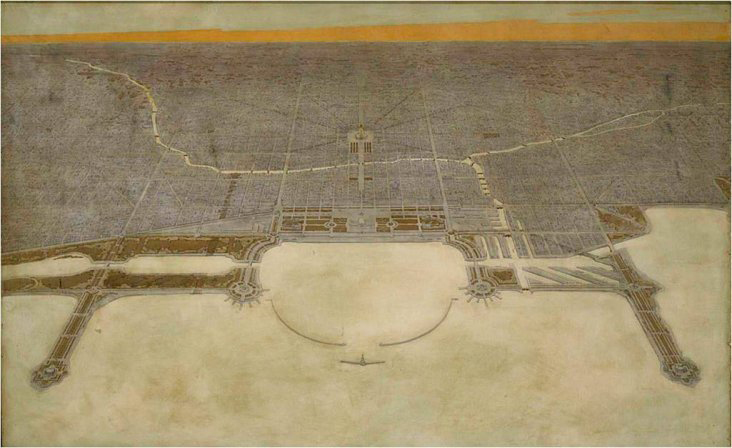

The Plan of Chicago, published in 1909 about two-thirds of the way through a sixty-year period when Chicago was the fastest growing city in the world, aspired to advance Chicago city and regional commerce and facilitate the best life for Chicagoans by means of the following themes and recommendations:

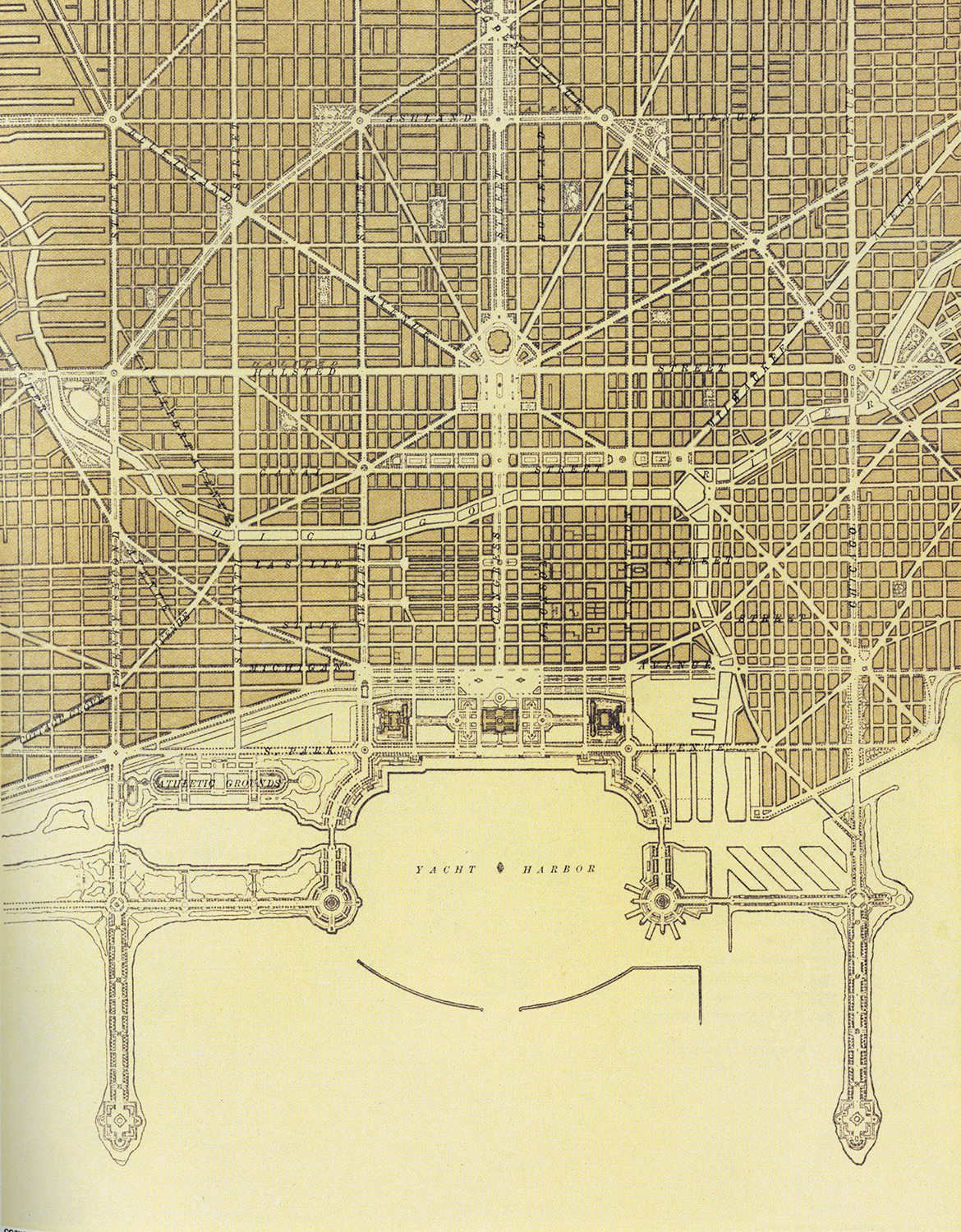

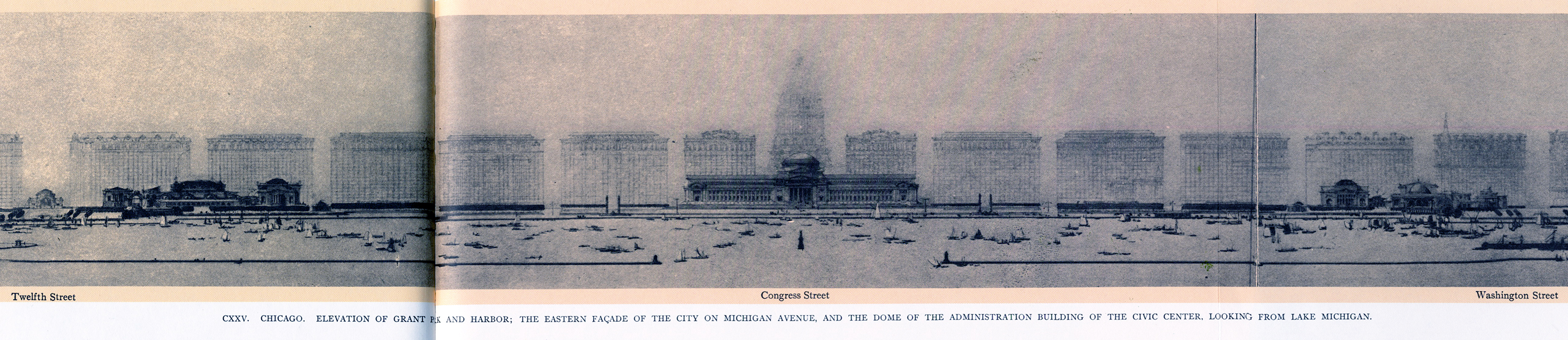

- Improving the Chicago lakefront and reserving it for public use

- Extending the existing park and boulevard systems, including designated forest preserves

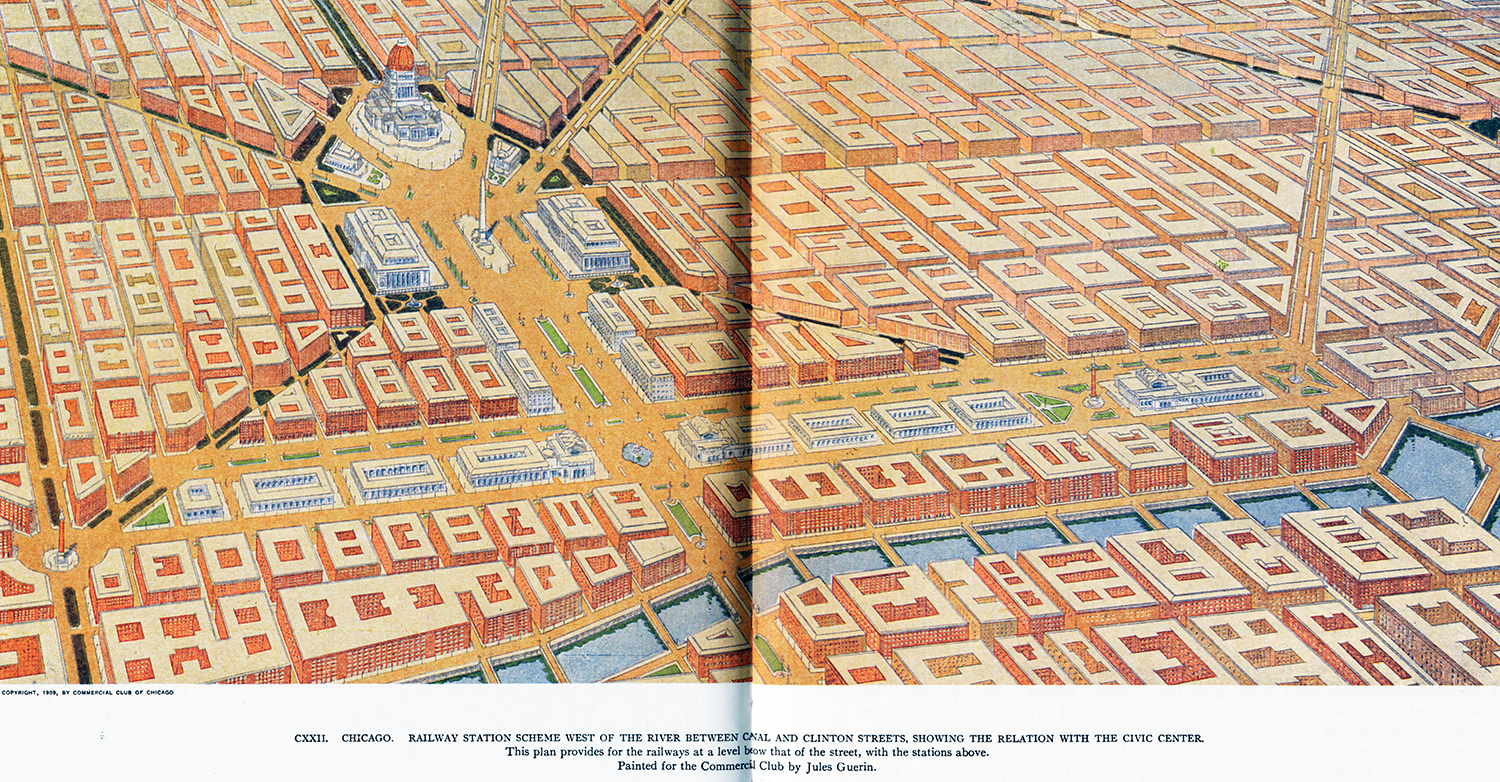

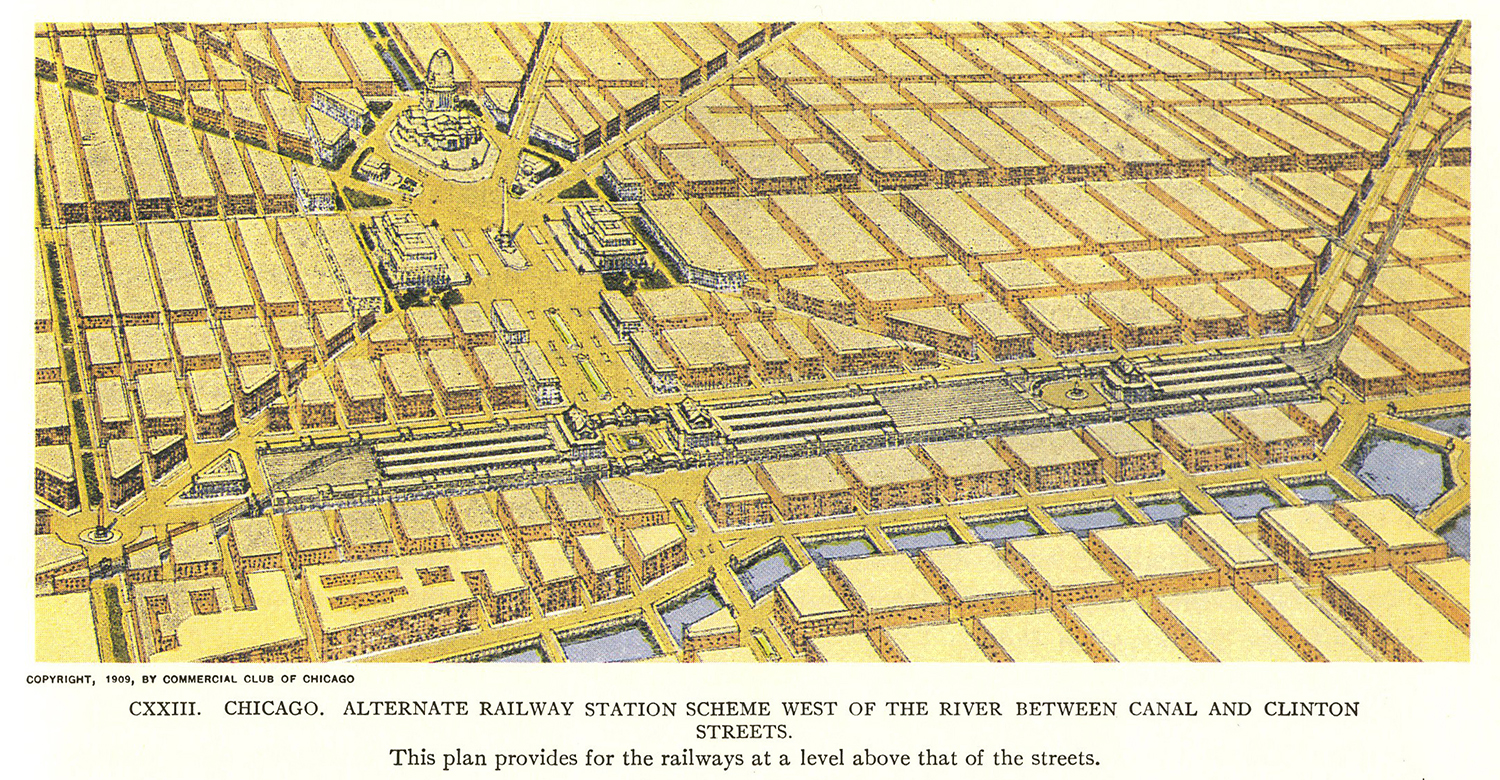

- Improving existing freight and passenger rail systems

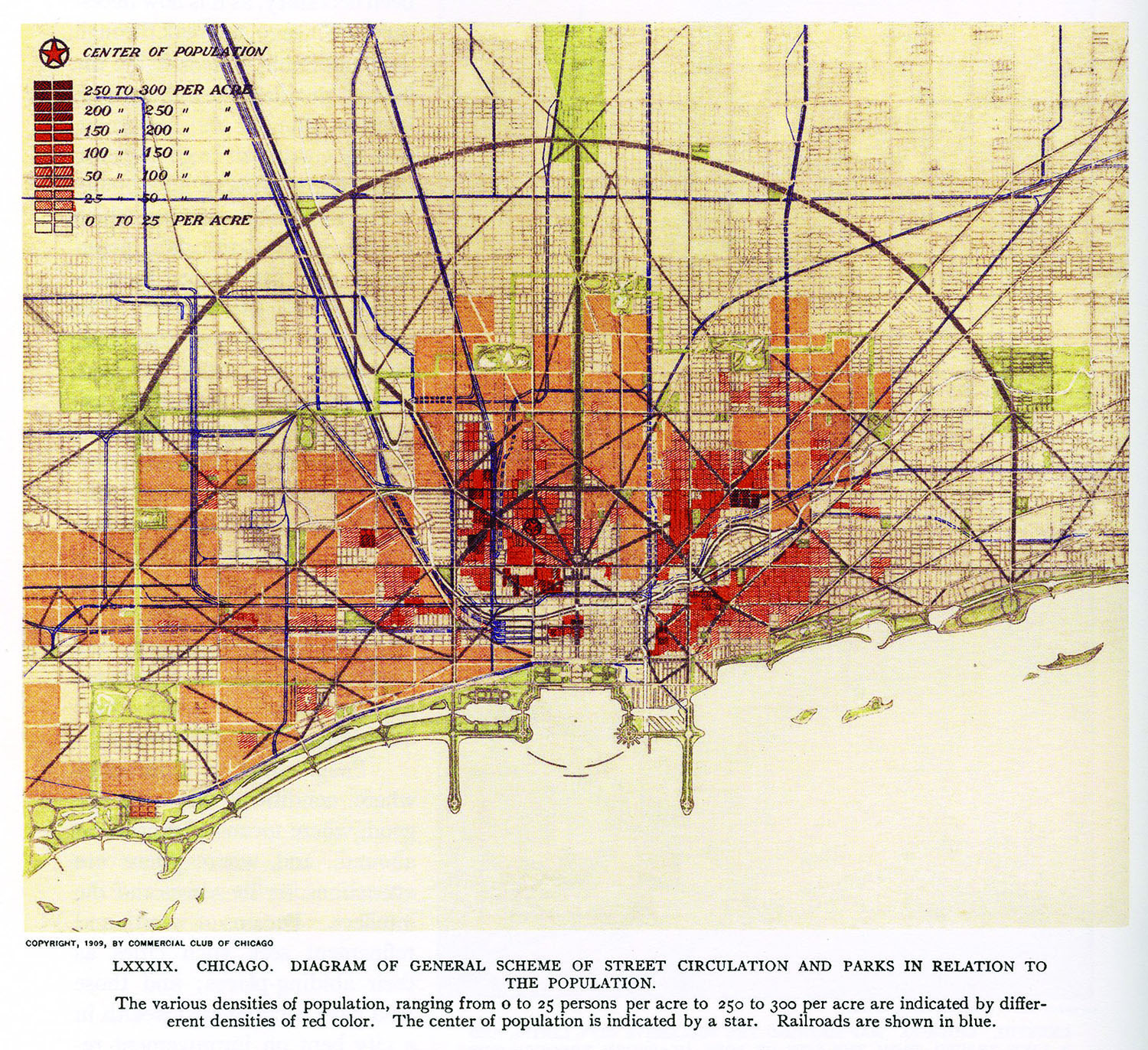

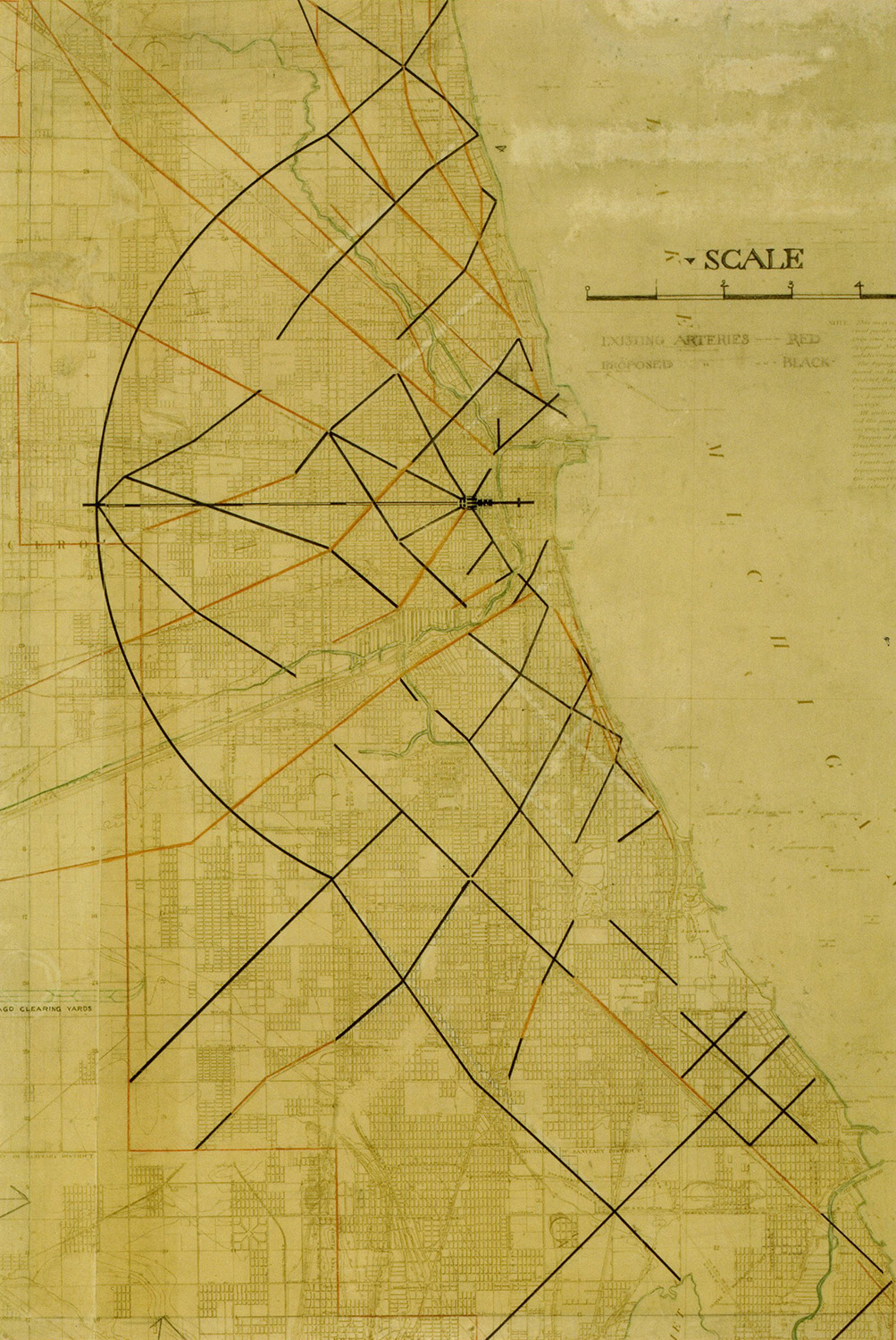

- Making a system of concentric thoroughfares in and for the Chicago region

- Arranging Chicago streets and avenues to facilitate movement to and from the central business district

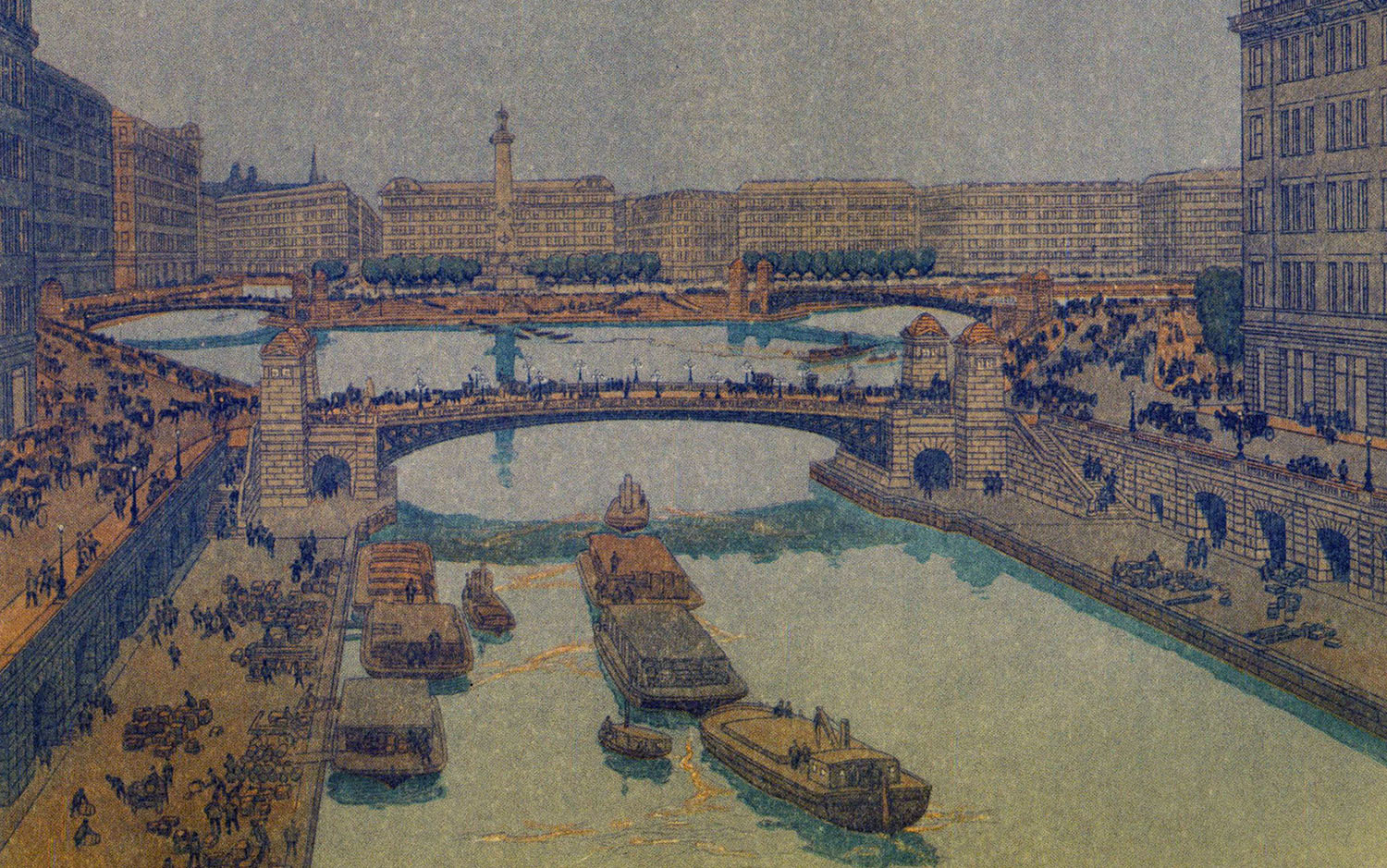

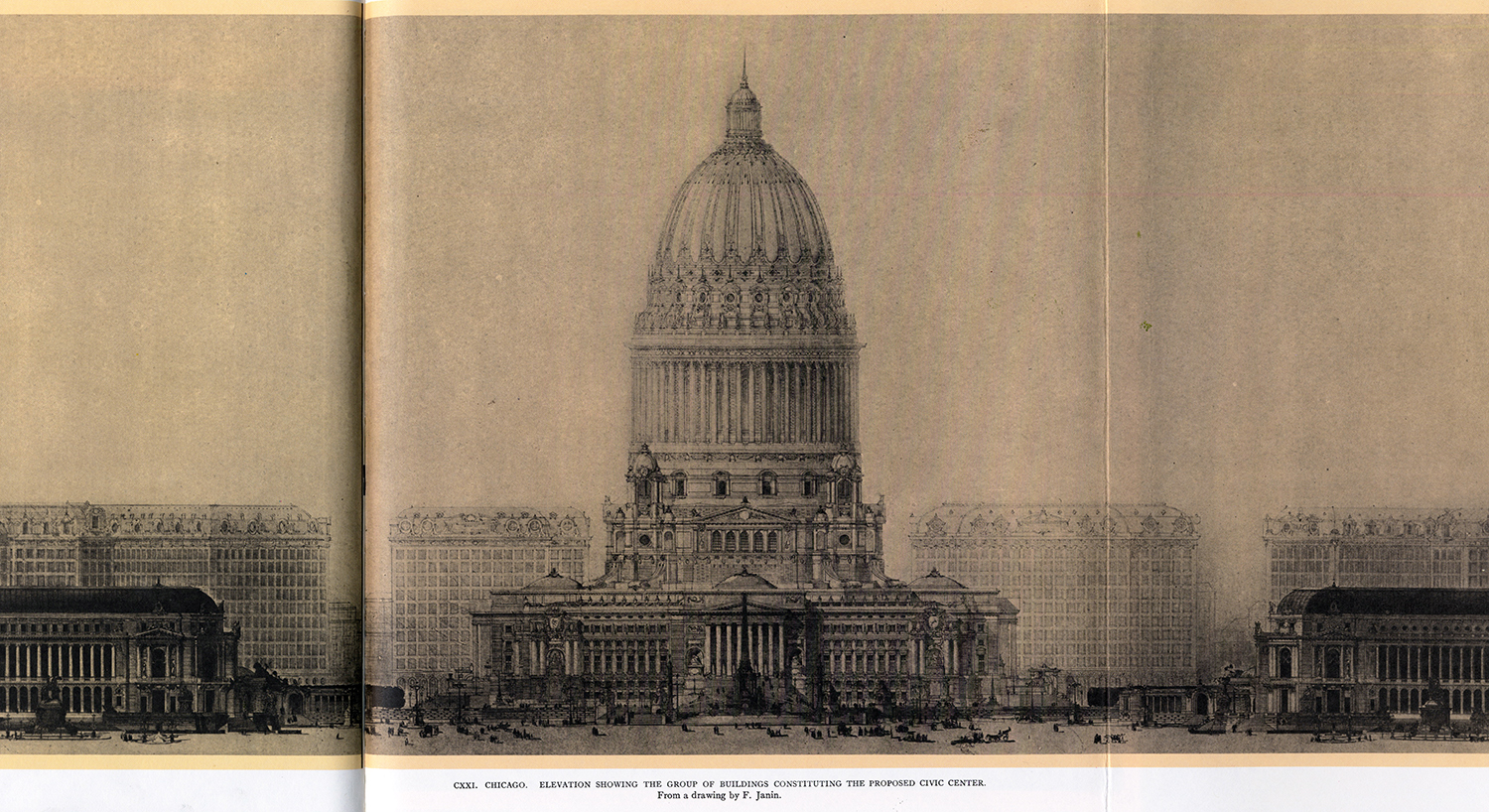

- Improving the business environment through beauty

- Making beautiful centers of civic administration and culture, so composed as to give narrative coherence to Chicago’s common life

Chicago has changed in the hundred-plus years since Burnham’s Plan; and today —in spite of growth in the historic center and a spectacularly photogenic lakefront— suffers from economic stagnation, financial crises, population decline, class segregation, and the loss of its middle class. (See also here.) In these less than favorable circumstances, The Notre Dame Plan of Chicago 2109 (hereafter Chicago 2109) does what Burnham himself did in 1909:

Second, to discover how those conditions may be improved;

Third, to record such conclusions in the shape of drawings and texts which shall become a guide for the future development of Chicago.

With proposals for metropolitan Chicago at the scale of the Burnham Plan itself —developing and extending ideas present in the Plan of Chicago, offering new suggestions of our own— Chicago 2109 is similarly comprehensive in ambition. But it is also as sober and prudential as is warranted for a foreseeable future of demographically based economic stagnation. In the era of economic limits dawning upon us, we think the ephemeral character and economic and environmental unsustainability of modernist architecture and urbanism will become increasingly apparent; and with durable wealth at a premium, we think the classical humanist urbanism of the Plan of Chicago and Chicago 2109 continues to have something substantive and good from which both Chicagoans and city lovers everywhere can learn and benefit.

As noted on the Home Page, there is an American precedent for urban design at this scale, for its loss, and for its recovery and subsequent development; and perhaps not coincidentally, it involved Daniel Burnham. The original 1791 plan for Washington DC by Pierre L’Enfant was severely compromised over the course of the 19th century and then, with the help of Daniel Burnham, corrected and extended by the United States Senate Park Commission (aka The McMillan Commission) in 1901 and thereafter. The so-called McMillan Plan and the Plan of Chicago were, of course, more or less contemporaneous; and the future they imagined was neither the future that occurred nor the future that most architects today imagine. Nevertheless, the Washington, DC we know today is a recognizable descendent of Pierre L’Enfant’s Plan of 1791, and is so because of the work of the McMillan Commission. To argue that the present and future relevance of the Plan of Chicago has passed is an ideological position rather than a necessary truth.